John Stepan Zamecnik

(1872–1953), a Cleveland violinist and composer of Czech ancestry who returned briefly to Prague to study composition, performance and conducting under Antonin Dvořák. Having performed as a young man with the Luna and Forest Hills Park orchestras, and written music for the Hermit Club revues, he was to play three seasons with the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra under Victor Herbert. Several of Zamecnik’s compositions for orchestra and band were performed in concert halls.

In 1907 he became music director of Cleveland’s then newHippodrome Theater, where he conducted music for revues and orchestra concerts. “The opening attraction at the Hippodrome,” writes William Ganson Rose in Cleveland: The Making of a City, “was Coaching Days, with music by John S. Zamecnik and book and lyrics by William J. Wilson. The great feature was the diving of horses into a large water-tank built into the front part of the stage.” A few years later, Zamecnik (Za-metz-nick) began composing incidental music with evocative and often memorable leitmotifs used by pit orchestras and organists in movie houses throughout the U.S.—with titles like “Mysterious Burglar Music,” “Storm Music,” “Pensive Mood,” “Oriental Veil Dance,” “Grief,” “Hurry Music,” “Entreaty” (a truly beautiful contribution to the violin repertory that evokes “a sense of longing, perfect for scenes when a lover is drifting away”), “Death Music,” “The Sacrifice,” “Le Chant des Boulevards” (a charming piece that conveys the feel of people “strolling briskly down sunlit avenues in a city”) and “Shadowed!” These were published by Cleveland-based Sam Fox, one of the first music publishing companies in the U.S. to issue film music scores. (For a generation the most widely performed “classical” music in America took place in movie houses!) When necessary, Zamecnik would tailor arrangements of his mood pieces to match whatever combination of instruments a particular movie house or chain had available.

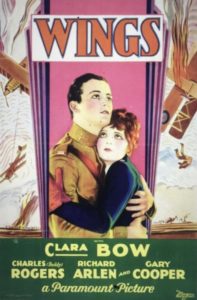

The fearless fliers of Wings soared to Zamecnik’s music. By Paramount Pictures – Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org

He also composed popular songs such as “Indian Dawn,” “Neapolitan Nights” and “Paradise.” After two of his piano pieces, “The Movie Rag” and “Maggie’s Ragtime Waltz,” were hits in 1912, Zamecnik reportedly stopped writing ragtime music “because his friends warned him (correctly in his day) that being a ragtime writer would seriously damage his reputation as a serious composer of classical music.” But he continued to conduct musical revues for Cleveland’s theater-oriented Hermit Club, which still survives, on Dodge Court, behind the Playhouse Square theaters.

Soon Hollywood began knocking at his door. J.S. Zamecnik would become one of the most sought-after specialists in the new genre of movie scores, enhancing the mood and ambiance of some 40 films. His music breathed life and color into everything from sea battles between the U.S. Navy and the Barbary Pirates in the 11-reel 1926 silent epic Old Ironsides . . . to the poignant humor of 1928’s Abie’s Irish Rose, an eagerly anticipated adaptation of the longest running play in the history of the American stage, about a marriage between a Catholic and a Jew. (“Rosemary,” Zamecnik’s song about the title character, with lyrics by the playwright Anne Nichols, became a spin-off hit.)

Zamecnik proved equally adept at tackling more serious subjects in such landmark cinematic productions as 1929’s Betrayal, the final silent appearance of the great German actor Emil Jannings; Redskin, the first Hollywood film to treat that term as a racial slur; and 1933’s The Power and the Glory, with Spencer Tracy and a screenplay by Herman Mankiewicz that is considered the prototype for Citizen Kane. For the 75th anniversary re-release on DVD and Blu-Ray of 1927’s Wings, a riveting drama about World War I fliers and the first film to win an Academy Award, Paramount had the original score recorded in stereo by a modern-day orchestra. (The newly recorded score is available on CD, as are examples of Zamecnik’s classic silent movie scene mood-setters.)

The opening theme of a popular circus march he composed for the 1935 film World Events would begin and end 20th Century Fox’s nationally distributed Movietone Newsreels for decades.

The Mont Alto Orchestra has recorded a CD of the short mood pieces he composed for silent films. Daniel Goldmark, professor of music at Case and director of the university’s Center for Popular Music Studies, authored the article on Zamecnik that appears in the online Grove Music Guide to American Film Music, and owns an extensive collection of the composer’s published work. He is also an authority on early music publishing in Cleveland and popular music that was big here in the early decades of the last century.